transitions before transitions

fall, flow, and fluctuations in grief

August: Piedmont, Italy

Change floats on the gentle breeze of the Langhe at the end of August: the sun is hot, but the chill on the wind hints at the colder days to come. The fertile land is pregnant with blackberries, figs, plums, peaches, and the first grapes of the season, but while some trees are green, others are already turning gold and red. The vineyards are abuzz with activity as the cantine prepare for the vendemmia.

It’s a portal, a liminal space, like that time of day when the sun starts dipping towards the horizon, but it’s not quite evening yet. When, in Langhe, a slow, sleepy biscia (grass snake) can cross your path, tiny lizards bask on stones in the last warmth of the day, pretending to escape as you walk past but not moving very far, when shy caprioli venture out of the woods to graze on the open pastures, when hares dart across the rugged hills, rushing to get home before night falls.

Nature is always shifting, subtly and almost imperceptibly but constantly. We don’t like transitions because they feel uncertain, but the perception of certainty is an illusion. The things we’re so sure of could crumble in an instant like a sand castle, and the only guarantee is death.

Grief feels like a constant transition, switching from one emotion to the next like anxious hummingbirds flitting desperately between flowers as the last heat of summer slips out of the evening light.

Joy brings sadness; sadness brings laughter; laughter brings joy, bringing sadness again…

Early September: Barcelona, Spain

Early autumn is arriving, but I live in Barcelona, and it’s still summer. I cling to the last days of heat, willing them to stay, knowing that change is as inevitable as death. The shifting seasons remind me more time is slipping by without her. More time is passing, and she’s still dead.

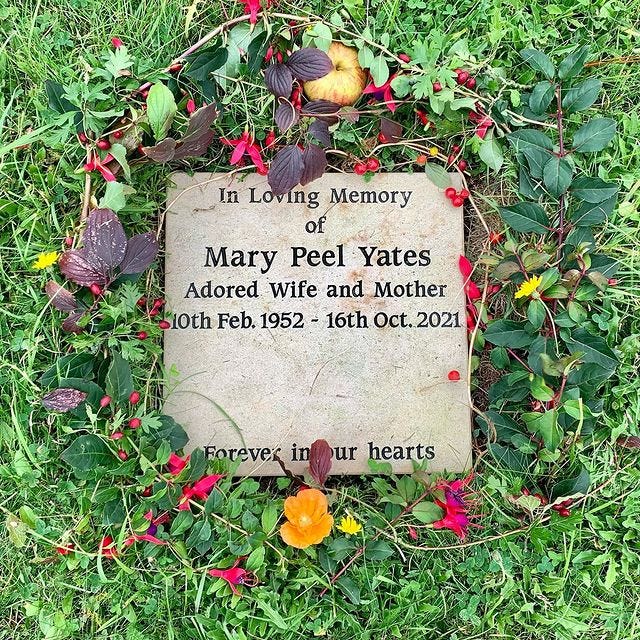

My mum loved to document the changing seasons in rural England on her Instagram profile. By now, she would have picked blackberries and made them into blackberry and apple crumble. There are still some in the freezer that she picked two Septembers ago, just weeks before she died. She was saving them for when I came home; she knew how much I loved blackberry and apple crumble. Perhaps it’s finally time to make it.

Late September: Dorset, England

Bristol airport was the last place I saw her. “I’ll see you in a few months,” I said, squeezing her tight, waving as she got into the car, not knowing a global pandemic was coming. It’s a weird place to have a last memory of someone, the liminal space of an airport car park. A place of transitions before transitions.

Ten years ago today, I flew from Brussels to Barcelona for a six-month work contract. Today, I’m flying to England, my first home, from Barcelona, my current home. I’ll land at Bristol airport, a place that was meaningless until I realised how full of meaningful memories it is. Every arrival and departure meant special time spent with my mum on the 1.5-hour car journey to or from the airport. Her smiling face lit up like the sun when I walked through the Arrivals doors as tears of joy welled in her blue eyes. Today, I realise I can’t remember what colour they were. I only know they were brighter than mine, like the sky on a sunny day. Mine are grey-blue, like clouds.

Almost exactly two years ago, I sat on this plane crying all the way. A kind lady swapped seats with me so I could sit with Max after he told her what had happened. I didn’t want to be the girl people felt sorry for. I wanted to be the girl whose mum was still alive.

Instead of her waiting at the gates I saw my father, brother, and his girlfriend who I’d never met before. They all hugged me, we all cried. I don’t remember the drive home. I just remember being enveloped in the all-encompassing stillness of death and the constant flurry of death admin; the anxious waiting for the call from the coroner; the undertaker’s advice not to see the body; the funeral arrangements.

I remember picking out the dress to cremate her in, weeping as I rifled through her wardrobe. After narrowing down the options, I called for a consensus. Max cooked and cleaned constantly to cope and I read the Buddhist Bardo at dinner every night. My aunt brought me weed and suddenly it was no longer a secret. The world turned upside down.

The Arrivals doors whoosh open, and as I walk through them, I find myself searching for her, knowing that she won’t be there, but hoping she might be anyway.

The title of this post was inspired by Alexandria Minor, breathwork teacher and host of ‘The Change We Need’ podcast. Follow her and subscribe for empowering, inspiring content.